The History of the Purple Line

(Adapted and updated from Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism,

a book by ACT's former president Ben Ross)

In 1989 Maryland governor William Donald Schaefer called for building two light rail lines with state funds. One would cross Baltimore, where Schaefer had long been mayor, from north to south, and the other would run on the Georgetown Branch, a 3-mile stretch of abandoned freight railroad that Montgomery County had bought the year before. The governor, whose motto had always been “do it now,” rushed forward headlong to build the line in his beloved Baltimore.

Montgomery County politicians wanted their trolley line too — they had purchased the right of way for that purpose — but the county's famously protracted planning processes delayed an official decision. After much public controversy, the Planning Board and County Council voted their approval. In January 1990, the light rail line between Silver Spring and Bethesda became part of the county's master plan. But by then, the promised state funds had disappeared in Baltimore cost overruns and an economic downturn.

The Georgetown Branch trolley was a transportation planner's dream. Not only did it run between two walkable downtowns that were the county's largest job centers, but at each end it would connect to a branch of the new Washington Metro. It could be built at ground level without running into traffic — most major roads already crossed over the old tracks on bridges. But the proposal faced lavishly funded opposition. The right of way ran through wealthy Chevy Chase neighborhoods and, worst of all, through the middle of the golf course of exclusive Columbia Country Club.

The state was now unable to build with its own money. Prodded by Delegate (later Maryland Attorney General) Brian Frosh, it began environmental studies needed to qualify for federal grants. But Doug Duncan, who had signed a pledge to oppose light rail, was elected county executive in 1994, and the new county council was closely split. All planning work halted and most observers thought the project was dead.

Back from the Grave

A small group of activists did not give up. In 1986, when the freight line closed, Harry Sanders, who had been the first executive director of Maryland Common Cause, and Ross Capon of the National Association of Railroad Passengers had teamed up to organize the Action Committee for Transit. The group's few dozen members proselytized for light rail before any audience they could find while relying on elected officials to provide political firepower.

After the election setback, Sanders realized a new strategy was needed. He set about organizing a coalition of organizations to support building the transit line. Only a threadbare coalition could be assembled at first. Business groups gave little more than token support; their attention was elsewhere, on a long-running struggle over whether to build a new expressway called the Intercounty Connector farther out in the suburbs. The most active allies were recruited from neighborhoods along the Beltway — there had been talk for years of widening this crowded highway that runs parallel to the light rail route, and civic leaders feared the project would resurface if transit was not built in the corridor.

After the election setback, Sanders realized a new strategy was needed. He set about organizing a coalition of organizations to support building the transit line. Only a threadbare coalition could be assembled at first. Business groups gave little more than token support; their attention was elsewhere, on a long-running struggle over whether to build a new expressway called the Intercounty Connector farther out in the suburbs. The most active allies were recruited from neighborhoods along the Beltway — there had been talk for years of widening this crowded highway that runs parallel to the light rail route, and civic leaders feared the project would resurface if transit was not built in the corridor.

The battle over light rail settled into a war of attrition. Opponents sought to make a bicycle trail, already planned to run alongside the tracks, a substitute for light rail. They convinced the county to build an “interim” graveled trail, and then made their slogan “save the trail.” The two sides battled for support of environmentalists and bicyclists. Retired ACT members haunted the state capital, watching for killer amendments hidden in the state budget by Columbia Country Club's lobbyists.

It was clear that overcoming the country club's money and connections would require not just the backing of a majority — that already existed — but a demonstration of overwhelming public support. It would also require mobilizing voters to counter the opponents' campaign contributions. The success of the Washington Metro system gave transit advocates a great tactical advantage — we could target supporters in large numbers by passing out leaflets at the stations. Before the 1998 primary election, ACT members distributed 20,000 scorecards that rated candidates on light rail and other transit issues. The new county council had a six-to-three majority for the light rail line, with one member crediting the scorecard for his margin of victory. The day after the new council was sworn in, it voted to ask the state to resume planning of the transit project.

From Trolley to Purple Line

Meanwhile, the State Highway Administration had restarted studies of adding more lanes to the Beltway around Washington. Required by federal law to consider transit alternatives, the study in early 1997 added an additional option suggested by ACT. This was an extended version of the Bethesda-Silver Spring light rail line, continuing eastward into Prince George's County and passing through the campus of the University of Maryland. The terminus of this route was soon fixed at New Carrollton, where it could connect to both a branch of the Metro and the Amtrak trains to New York. With five other colors already spoken for on the map of the Washington Metro, the project became known as the Purple Line.

As the study proceeded, transit options increasingly became the focus. Engineers were finding that widening the Beltway would be difficult and extraordinarily expensive, and Governor Parris Glendening's pursuit of his smart growth agenda brought a higher priority to transit. A political battle was raging over the Intercounty Connector after the governor stopped work in 1999; environmental groups that had earlier hesitated to offend members in Chevy Chase now lined up behind the light rail line as a major transportation project they could favor.

Voters, by a substantial majority, favored the project, but in the more affluent sections of the county latent support was drowned out by the noisy opposition. Even the Purple Line's most ardent backers underestimated the public's enthusiasm for it. A color leaflet showing the new line inserted into Washington's iconic subway map was well received, so in March 2001 ACT threw all its resources into passing out 30,000 copies at Metro stations. Hope that a coupon on the rear of the flyer would attract a few new members grew into astonishment when 120 of them were clipped out and returned with $10 dues checks.

To build on this success, ACT turned to the Purple Line's other established base of grass-roots support and distributed the leaflet door to door in communities along the Beltway. Each copy was accompanied by a letter from a civic association leader explaining why light rail was needed to stave off the threat of highway widening. The favorable response from homes close to the noisy interstate was no surprise, but unexpectedly just as many new members were recruited from other sections of those neighborhoods. So ACT moved on to other areas, distributing more than 50,000 letters over five years and reaching a peak membership of more than a thousand.

At the Center of Public Debate

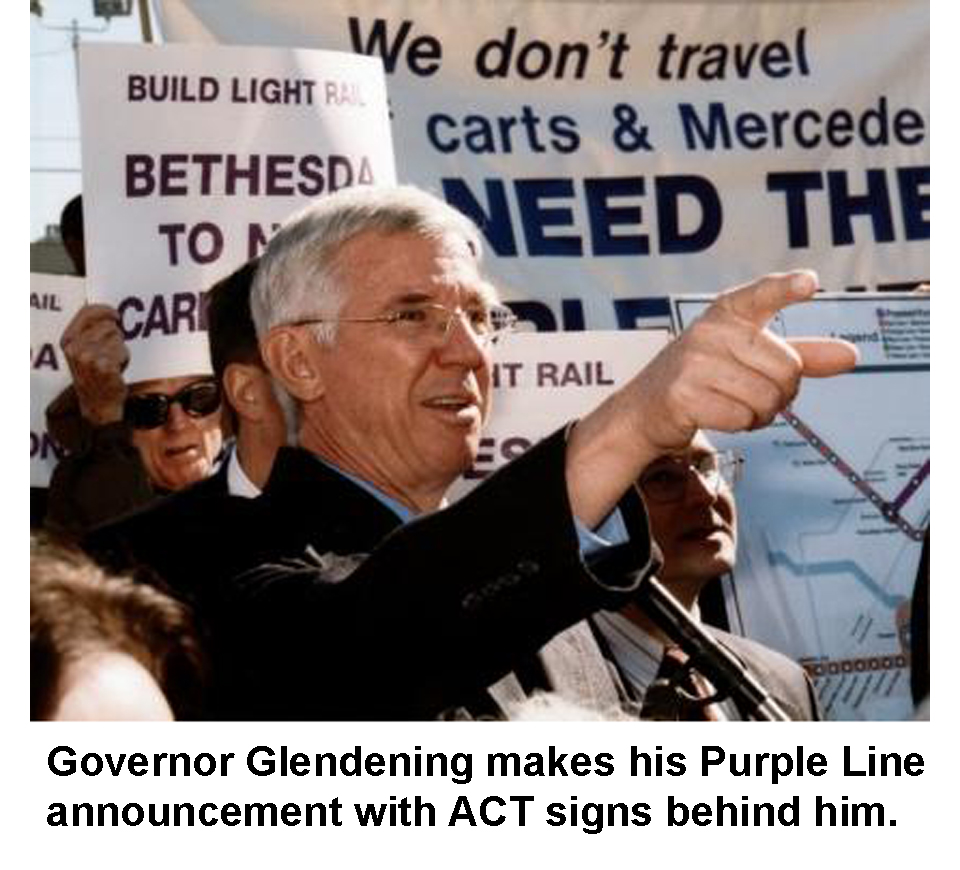

Governor Glendening now swung strongly behind the Purple Line. Studies showed that alternatives suggested by Columbia Country Club and its political allies, such as an underground subway outside the Beltway, a shallow “cut-and-cover” tunnel, or an elevated Metro loop above the Beltway, were either impractical or impossibly expensive. In October 2001 the governor gave the route from Bethesda to New Carrollton a high-profile endorsement.

Business groups, no longer seeing the light rail line as pie in the sky, became strong and active supporters. Planning went into high gear, but the victory was short-lived. In 2002 Maryland elected a Republican governor, Robert Ehrlich, who opposed the project.

Ehrlich, under heavy pressure from business lobbies, did not stop the project entirely. But planning of light rail ground to a near-halt while a new low-cost bus alternative was studied. At the same time, the new governor moved quickly ahead to build the Intercounty Connector at a cost of more than $2 billion. This expensive roadway gobbled up funds that might have been used for the Purple Line, but at the same time it greatly strengthened the project's political position. With the highway no longer in question, the transit line became the top transportation priority of suburban business groups.

In 2006 Governor Ehrlich was defeated for re-election by Martin O'Malley, mayor of Baltimore and a Purple Line backer. By now an extraordinary coalition had lined up behind the project. It included business, labor, environmentalists, ethnic minorities, and many neighborhood associations. Outspoken support had emerged even in the Chevy Chase neighborhoods where opposition was strongest. The “save the trail” slogan was undercut by a clear endorsement from the Washington Area Bicyclist Association. Most of the few remaining opponents among elected officials now reversed their positions, and the councils and executives of both counties gave unanimous support.

The consensus was reinforced by the gubernatorial rematch election of 2010. Ehrlich had allowed himself to be quoted saying that “it will not go through the Country Club” and O'Malley was able to champion a populist cause that won support from business. The Purple Line was a central issue in election-year debates, cited by Washington-area business groups in offering an unusual endorsement to the Democratic candidate. O'Malley swept to a landslide victory, and work on the project began to move steadily ahead.

In October 2011, the federal Dept. of Transportation approved the project's move into the preliminary engineering phase. In March 2013, the Maryland legislature passed a transportation funding bill, with one of its main goals funding the Purple Line. In April and August, Governor O'Malley budgeted $680 million of the new revenue for the Purple Line, bringing the total state commitment to $900 million.

Meanwhile, in June 2013, the biggest political obstacle to the Purple Line was removed from the scene when Columbia Country Club dropped its opposition. An exchange of real estate will move the light rail tracks 12 feet to the side and allow the country club's golf course to keep tees at the most desirable locations.

In March 2014, the Federal Transit Administration issued its Record of Decision approving the project. President Obama's 2015 budget recommended the project for a Full Funding Agreement providing $900 million in federal construction money. The first $100 million of the construction money was appropriated in the omnibus spending bill passed in December.

More Obstacles to Overcome

But the election of Governor Larry Hogan in November 2014 brought new uncertainty. The request for proposals for construction and operation of the light rail line, originally scheduled to be issued in January 2015, was repeatedly delayed. The Maryland legislature continued to strongly support the project; construction money was appropriated in the 2016 budget with a clause that forbids transfer to any other use.

After a series of delays in the governor's decision, he announced on June 25, 2015 that the project will go forward with some cost savings and a somewhat greater financial contribution by Montgomery and Prince George's Counties. In March 2016, a "Purple Line Transit Partners" team led by Fluor Construction was selected to build and operate the project. The contract was approved by the state Board of Public Works on April 6.

But Chevy Chase residents whose houses back onto the rail right-of-way had filed a lawsuit. On August 3rd, 2016, four days before the scheduled signing of a $900 million federal grant agreement, U.S. District Court Judge Richard Leon, also a Chevy Chase resident, halted the construction of the Purple Line. The judge questioned the project's ridership estimates and demanded that a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) be conducted before the project can proceed to construction. Because Judge Leon delayed deciding on other issues raised by the plaintiffs, it was not possible to appeal this decision until the following June.

The federal Appeals Court took swift action when the case finally reached it. On July 17, 2017, it issued an emergency order that suspended Judge Leon's stop-work order. The signing of the federal grant agreement and groundbreaking take place on August 28.